CVE-2024-53845 - A Small Crypto Detail, Found by Accident

Cryptography CVE AES CBC SecurityEngineering ESPTouch

This Wasn’t the Plan

This vulnerability wasn’t found during a formal security audit. It wasn’t part of a red team exercise. And it definitely wasn’t me hunting for CVEs.

About a year ago, I was working on a completely different side project. Like many side projects, it involved IoT devices, Wi‑Fi provisioning, and the usual “let’s read the code and see how this actually works” routine. At some point, I found myself reading through the ESPTouch v2 implementation.

What actually pulled me in wasn’t security at all - it was curiosity. ESPTouch is one of those protocols that feels a bit magical: somehow a device manages to pass Wi-Fi credentials to a headless device that has no screen, no keyboard, and no prior trust. I wanted to understand how that trick works and the security behind it.

So I started reading through the ESPTouch v2 implementation. Honestly, I wasn’t expecting to find anything. ESPTouch is widely used, battle-tested, and maintained by a reputable vendor. It’s embedded in countless consumer and industrial devices.

The Moment Something Felt Off

ESPTouch is Espressif’s implementation of SmartConfig ‑ a provisioning mechanism that allows headless IoT devices (no screen, no keyboard) to receive Wi‑Fi credentials over the air.

This technique is widely used across the ESP ecosystem, including ESP32, ESP32‑S2, and ESP8266, and is common in smart plugs, bulbs, sensors, and other consumer IoT devices.

Earlier versions of the protocol (ESPTouch v1) didn’t have encryption at all. ESPTouch v2 was a step forward: it introduced optional encryption using AES‑128 in CBC mode to protect credentials during provisioning. I was most interested about the keys exchange protocol and its security aspects.

Curious about how the “magic” works, I started reading the code of the demo Android application provided by Espressif, the one that broadcasts home Wi‑Fi credentials using the ESP Android SDK.

And then, completely by chance, I looked for the Initialization Vector (IV), and eventually realized: there isn’t one you can configure. Digging deeper showed that the IV is hardcoded to all zeros. Always, for every encryption, for every device. For the entire lifetime of the product.

At first glance, nothing breaks. The code works. Devices provision successfully. Wi‑Fi credentials get delivered. Which is exactly why this kind of issue survives.

Why This Isn’t an RCE (and why it still matters)

Let’s be clear upfront: this is not an RCE. No shells are popping. No memory corruption. No immediate device takeover.

But security is rarely about a single bug in isolation. It’s about context: where the code runs, how often it’s used, who can observe it, which type of information we are trying to encrypt and what the surrounding attack surface looks like.

In this case, the vulnerable code sits on a critical path: device provisioning, where we encrypts the user’s password (most of the time short text). It runs before trust is established, over the air, often in uncontrolled environments, and is executed by devices that may live in the field for years.

So while nothing “explodes” on impact, the conditions are exactly where subtle cryptographic mistakes tend to matter.

What the IV Is (and why it exists)

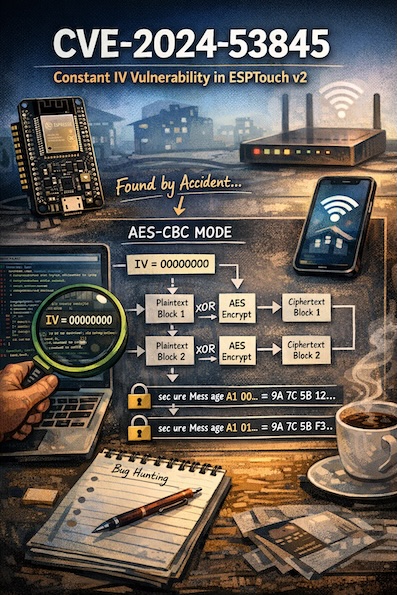

AES is a block cipher: it encrypts fixed-size blocks of 16 bytes. When encrypting longer messages, a mode of operation is required to define how those blocks are chained together.

In CBC (Cipher Block Chaining) mode, each plaintext block is XORed with the previous ciphertext block before encryption. This creates a dependency between blocks and prevents identical plaintext blocks from encrypting to identical ciphertext blocks - except for the first one.

And that first block is the key problem.

Since there is no “previous ciphertext” for the first block, CBC introduces the Initialization Vector (IV). The IV acts as a synthetic, one-time “previous block” whose sole purpose is to randomize the encryption of the first plaintext block.

The security requirement is simple:

The IV must ensure that encrypting the same plaintext twice produces different ciphertexts.

The IV does not need to be secret. But it must be unpredictable (or at least unique) for every encryption under the same key. When this requirement is met, CBC encryption is probabilistic. When it is not CBC quietly becomes deterministic.

Why a Constant IV Breaks This

With a fixed IV, the first ciphertext block is computed as:

- the same plaintext block

- XORed with the same IV

- encrypted with the same key

Mathematically, CBC encryption is defined as:

\[\left\{ \begin{array}{cl} c_i & : {E_{key} (P_i \oplus C_{i-1}) } \\ c_0 & : {E_{key} (P_i \oplus IV) } \end{array} \right.\]This produces the same ciphertext block every time.

Because CBC chains blocks together, this determinism propagates forward:

- identical first plaintext blocks → identical first ciphertext blocks

- shared prefixes → shared ciphertext prefixes

At that point, encryption no longer hides structure, it leaks it.

This is exactly the behavior observed in ESPTouch v2.

A Simple Example That Explains Everything

Imagine two Wi‑Fi passwords:

SecureMessageA100SecureMessageA101

They share the same first 16 bytes. AES works in 16‑byte blocks. With a constant IV:

- The first ciphertext block for both passwords will be identical

No keys are broken. No crypto is cracked.

But an observer can immediately learn something about the plaintext, that the two secrets share a common prefix. Suddenly, this turns into something much more interesting than a theoretical crypto nit.

When It Gets Worse: Real‑World IoT Behavior

In many real deployments:

- AES keys are shared across devices

- Firmware lives for years

- Provisioning traffic can be captured passively

When encryption becomes deterministic, this immediately enables information leakage. An observer can tell when two provisioning attempts share the same plaintext prefix. For example, Wi-Fi passwords with identical first 16 bytes will produce identical ciphertext blocks.

In deployments where the encryption key is static or recoverable (a common pattern in IoT ecosystems), this determinism can further enable offline analysis, including dictionary-style attacks against captured traffic - without interacting with the device and without triggering any alarms.

This combination of guaranteed information leakage and context-dependent exploitability is why the issue was assigned CVE-2024-53845, even though nothing “explodes” on impact.

Confirming the Suspicion

One thing I like about this bug is how easy it is to demonstrate.

You don’t need hardware. You don’t need special tools. Just Android Studio.

- Encrypt the same input twice → identical output

- Encrypt two inputs with the same 16‑byte prefix → identical ciphertext prefix

Once you log the encrypted buffer, the problem explains itself.

Disclosure and Outcome

After confirming the behavior, I reported the issue to Espressif with a detailed write‑up.

To their credit, the process was professional and straightforward. In December 2024, the issue was publicly disclosed and assigned CVE‑2024‑53845.

More importantly, the protocol documentation was updated:

Starting with SmartConfig v3.0.2, ESPTouch v2 now supports using a random IV for AES encryption. For backward compatibility, the default behavior remains unchanged: if the random-IV option is disabled, the IV is still set to zero. When enabled, a fresh random IV is generated and transmitted as part of the provisioning flow.

The documentation also explicitly calls out the trade-off: enabling a random IV slightly increases provisioning time, since the IV must be sent to the device. The provisioning device detects whether random IVs are in use via a flag in the provisioning packet.

In addition, the demo application was updated to reflect this change, allowing users to opt into the more secure behavior with minimal effort.

The Bigger Lesson

In cryptography, the devil is almost always in the small details. Strong primitives don’t guarantee strong security!