Writing Tests as a Tool to Enhance Code Readability

testing CleanCode SoftwareEngineering

TL;DR

I live by a simple rule: if writing tests for the code I’ve created feels like a challenge—something’s not quite right.

Back in the day

Early in my career, I faced a task: develop a program automating ticket creation in our task management system. The goal was to scan a task list, open a new ticket for each task using a predefined template, and establish dependencies between various tasks, reflected in the relationships between distinct tickets.

With the clock ticking, my team leader and I decided to first build a working system. We’d let a teammate give it a once-over in a code review, and then, when the stars aligned, we’d dive into writing tests.

The code performed admirably, executing its designated task effectively. However, the challenge arose during the creation of straightforward tests, consuming an inordinate amount of time. It demanded an intimate familiarity with the code—objects constructed from CSV files with specific structures (discerning the structure required delving into the relevant code snippets). And before even checking if everything worked, we had to patch up private functions tied to a maze-like family tree of objects. Oh, and all this happened before we even put the implemented features to the test.

Even in the initial code review stages, an unsettling feeling lingered. The review process proved time-consuming. Preceding the exhaustive rounds of comments and corrections, I found myself explaining the code’s design and architecture in face-to-face meetings—an unusual step.

The cognitive load and steep learning curve for a simple test proved overwhelming. In the end, writing tests turned into a big job on its own.

Tests resistant to easy creation and maintenance will inevitably become a burden. Over time, the effort invested in writing and maintaining tests may surpass that required for developing new features.

The code went out of control.

Introduction

There has been much written about the importance of writing tests—the way they provide confidence for refactoring existing code, serve as documentation for existing code, and serve as a live example for its use. Much has also been said about the importance of readable code. In short, unreadable code is a technical debt that, over time, significantly impacts the development pace—trivial tasks become challenging to implement, increasing the learning curve for new developers.

While we all aim to produce code that is easily understood, the path to acquiring this skill, enhancing existing code, and determining the readability of code remains uncertain, along with the methods to measure it.

Writing a “clean code” is a skill that requires practice and openness to criticism from colleagues. In this blog, I will propose a simple technique for improving code readability through writing tests.

How Do You Measure Code Readability?

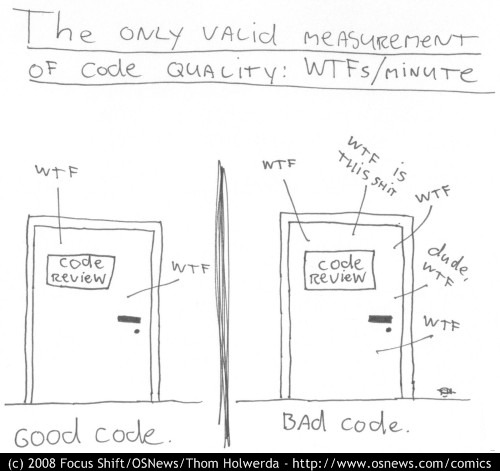

The bad news is that there is no definitive way to calculate how readable a specific piece of code is. Linters can be used to check code structure and provide general comments (line length, long variable names, excessive use of arguments or variables, etc.), but undoubtedly, the best way to get a sense is through code review by a colleague and understanding how much time it takes for them to comprehend it (or, in a less formal way, the number of “WTFs/Minutes” metric).

The problem is that code review is a somewhat costly resource. It requires someone else’s time, and there isn’t always someone available to perform the code review. Sometimes it takes time to find someone willing to review the code.

You can always try to do a code review on your own code, but from my experience, it’s challenging to review code you wrote. We are not objective towards our own code; we have invested hours of planning, thought, and implementation into it, and like many things we invest time in, we are “attached” to it. Therefore, it’s challenging for us to be objectively critical of it (making it difficult for us to accept criticism from others). Only with some time apart can we attempt to approach the code and look at it with a critical eye (though it somewhat misses the goal of writing clean code as quickly as possible).

So, what can be done to improve the readability of the code we wrote without code review?

The Connection Between Tests and Code Readability

I have a rule of thumb: if you find it challenging to write tests for the code you wrote - something smells fishy here…

Many times, when we write tests, it’s the first time we “encounter” our own code. While writing the tests, we need to deal with the code we wrote by using it for the first time, acting as consumers of it. This perceptual shift causes us to look at our code more objectively from the outside. Writing tests should be a simple and somewhat trivial task—if we struggle, we likely missed something.

When we write tests, we are essentially checking the public interface we implemented and asking ourselves the following questions:

- Is it easy to test the public interface?

- Does the test use implementation details to function? For example, do I need to use mocks/patches that expose the internal implementation to test the code?

- Do I need to use a large number of asserts in a single test to check if the code does what is expected of it?

This is a partial list of examples, each of which is a red flag indicating that we missed something essential in the design: perhaps it would have been right to break down the function into smaller functions, so that each function has only one defined task? Does the code need to provide a clear indication of success and failure?

The skill of writing good tests is a topic for another blog post. What’s important to note is not to ignore red flags and to change the code so that writing tests is as simple and clear as possible.

From my perspective, this is an iterative process: I write code that performs the task and only then move on to writing tests. When I approach writing tests, I change the perspective—I am now the consumer/user of the code I wrote (in the public interface) and I am encountering it for the first time. Throughout the process, I ask myself all the questions mentioned above (or notice when I “get stuck” writing the test), and if needed, I also change the existing code and go back to writing the test.

Conclusion

The process of writing tests acts as a litmus test for the clarity and simplicity of your code. If writing tests feels like a challenge, it signals potential issues in the code’s design and readability.

While the process of writing tests may lengthen development time, it provides a baseline for a clean, readable interface.

Ideally, we would work with Test-Driven Development (TDD), writing tests before production code. However, in reality, the iterative approach of writing tests post-implementation is a pragmatic compromise for many software developers.

As we get accustomed to writing tests, the process becomes more straightforward, offering a worthwhile investment in clean, readable code that is easy to revisit and update. As we write tests earlier in the development process, the task becomes easier. When we approach new code with an already established testing mindset, the process becomes simpler and shorter over time, making it a valuable investment in the long run.